Rabbi Grossman, Head of School

Chidushim B’Chinuch—Insights into Education

Fourth of an Ongoing Series

The reading of Kohelet, the book of Ecclesiastes, on the holiday of Sukkot remains one of the great mysteries of the Jewish liturgical year. The just-completed Festival of Booths is the most joyous of the Jewish year, and yet it is during this holiday that we read the melancholy megillah that speaks of the vanity of life. My suspicion is that Ecclesiastes is read at this time of year because of its focus on the cyclical nature of time:

Generations come and generations go,

but the earth remains forever.

The sun rises and the sun sets,

and hurries back to where it rises… (Ecclesiastes 1:4-5)

There is a time for everything,

and a season for every activity under the heavens:

a time to be born and a time to die,

a time to plant and a time to uproot… (Ecclesiastes 3:1-2)

Invoking the idea of cyclical time is the perfect way to conclude the new-year season, as we begin again our annual calendrical cycle.

Cyclical time is also featured in the Torah portion this week. In the first chapter of Genesis we hear of the creation of the sun and the moon, which are created to mark various cycles of time: the sun marks the 24-hour cycle of the day, as well as the 365-day cycle of the solar year, while the moon demarcates the 30-day cycle of the lunar month. As well, the parasha tells us of another cycle, the 7-day week, which God has embedded in creation (though not indicated by any phenomenon of nature). The message that emerges from these biblical sources is that cyclical time is fundamental to the natural world, the Divine plan, and, consequently, the human psyche.

Because of the centrality of cyclical time in the human mind, educators have developed schools and curricula that follow cyclical rhythms. This is one of the reasons why, for example, we have the cycle of the academic year (fall-spring), which is then divided into three internal trimester cycles. In Quebec, we even use the term cycle to subdivide elementary and high school learning (e.g. Cycle 1 (Kindergarten- Grade 2), Cycle 2 (Grades 3-4)).

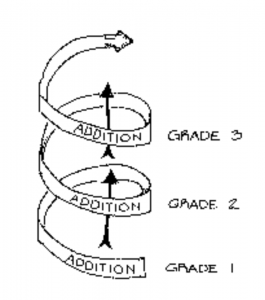

Spiral Curriculum

On a more sophisticated curricular level, the cyclical principle manifests itself in what is called, in educational parlance, The Spiral Curriculum. This methodology involves teaching the same idea or concept in a recurring cycle, each time moving up a level, so that students are learning in an upward spiral. At Akiva, for example, our Math curriculum is spiraled, so that every year students learn, for example, multiplication, but with increasing sophistication each time they return to the topic. Our French curriculum, too, is spiraled, with concepts such as irregular verbs and tenses revisited in an ongoing and elevating rotation.

Cyclical learning has great advantages over its alternative, linear learning. In linear learning, once a topic is taught, it is abandoned and never revisited; moving forward, the next topic is then explored. Linear learning appears, at first glance, to be more efficient—why go back to a subject that has already been covered? Moreover, students who learn in a cyclical system often complain that the material is repetitious, and one often hears a chorus of, “Didn’t we learn this already?” Indeed, Kohelet himself protested that the cyclical nature of the world makes life feel meaningless:

Futility of futilities, all is futile!

What has been will be again,

what has been done will be done again;

there is nothing new under the sun. (Ecclesiastes 1: 1, 9)

To address these very real objections, at Akiva we include linear learning alongside our cyclical curriculum, making sure each year to introduce new material that we know our students have never encountered before. Overall, however, it is the cyclical approach that dominates. Cyclical learning ensures that concepts are continuously reinforced, and does not assume that students have mastered a subject just because the unit or year is over. It allows students to grow, for even students who do not understand a concept the first time around are given a second, third, and fourth chance to succeed when the topic is encountered the next time around. As the Torah teaches, when we follow cyclical rhythms, we are in touch with the most human, most natural, and most Godly parts of ourselves.

The verses from Kohelet chapter 3 quoted above were set to music by American folk singer Pete Seeger in the 1950s, then recorded and popularized by the group The Byrds in 1965. Many people are unaware that this folk/pop classic is taken directly from the Hebrew Bible (with the addition of a 3-word chorus “Turn Turn Turn!” that became its title). You can listen here:

The verses from Kohelet chapter 3 quoted above were set to music by American folk singer Pete Seeger in the 1950s, then recorded and popularized by the group The Byrds in 1965. Many people are unaware that this folk/pop classic is taken directly from the Hebrew Bible (with the addition of a 3-word chorus “Turn Turn Turn!” that became its title). You can listen here: