Rabbi Grossman, Head of School

Chidushim B’Chinuch—Insights into Education

Eighth of an Ongoing Series

When I moved to Massachusetts many years ago, one of my first stops was the Granary Burial Ground, located in downtown Boston. Tourists and residents alike make pilgrimages to this cemetery to pay respects to American heroes such as Paul Revere, Samuel Adams, and John Hancock, all of whom are interred in its earth. I, however, was there to visit the final resting place of a woman who had inspired me since the time I could first read a book: I went to pay homage to Mother Goose.

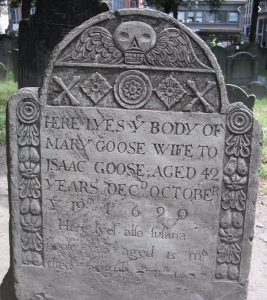

Headstone of Mother Goose in the Granary Burial Ground, Boston.

Mary Goose, who died in 1690 and is buried in the Granary, is deemed the Original Mother Goose by purveyors of the tourist trade in Boston. Scholars dispute this claim, but it is charming nevertheless to see young and old gather about her headstone, recalling the rhymes and fairy tales of childhood.

Historically, the person who can most legitimately lay claim to the title of the real Mother Goose was neither woman nor waterfowl but Charles Perrault, who published a collection of eight fairy tales in French in 1697 entitled Histoires ou contes du temps passé, avec des moralités: Contes de ma mère l’Oye (Stories or Tales from Times Past, with Morals: Tales of Mother Goose). His book included favorites such as Sleeping Beauty, Cinderella, and Little Red Riding Hood, classics that are still popular today. Indeed, they were already popular in the 17th century; Perrault merely retold well-known folk tales that were in wide circulation already in his day.

Psychologists, anthropologists, and educational scholars have long understood the importance that fairy tales play in child development. When we incorporate fairy tales into our curriculum at Akiva, such as in our Grade 2 Readers Theater last week, we do so both to familiarize our students with the terrific tall tales of yore and to provide them with the educational and emotional scaffolding that fairy tales provide.

Fairy tales allow children a safe space in which to explore and experience difficult concepts that they will encounter in real life. Good and evil, fear and uncertainty, anxiety and danger, are all features of fairy tales—and of everyday existence. But in fairy tales, these troubling tropes take place “a long time ago in a faraway land,” that is to say, in a place and time where and when they can do no harm to the young reader. As children grow up they will encounter witches, wolves, and foxes who will connive to injure them, if not physically, then emotionally and financially. Fairy tales warn children that there are bad people in the world, and to be on their guard against those who may not have their best interests in mind. These messages are also delivered in ways that children are most likely to absorb. Like the title of Perrault’s book, fairy tales have morals, but they are generally not moralizing and preachy. Lessons are learned through seeing the natural consequences that happen to the characters.

Because of the strong messages fairy tales deliver, the stories can often be frightening.

Some contemporary parents and educators believe that classic fairy tales are too intense for young children; a 2012 study found that nearly half of the 2,000 parents surveyed would not read Rumplestiltskin to their children because it contains kidnapping and execution. The version of Snow White that is in common circulation today still involves a wicked woman who poisons an innocent girl, though it is far less gruesome than the earlier rendition that appears in the anthology of the German folklorists Wilhelm and Jacob (“The Brothers”) Grimm. However, the enduring popularity of fairy tales coupled with academic research argue that fairy tales are a healthy way to expose children to scary situations: only in a fairy tale can you, at any point, flip to the last page to discover that everyone lives happily ever after.

Fractured Fairy Tales began as a segment of the Rocky and Bullwinkle Show (1959-1964).

Not a Damsel in Distress: George Lucas created the smart and powerful Princess Leia, but still set his fairy tale “A Long Time Ago in a Galaxy Far, Far Away,” an updated version of “A Long Time Ago in a Faraway Land.”

Fairy tales also inspire children with valiant heroes, charming princesses, and gallant princes. These characters challenge their readers to strive to help and rescue others, and to be young men and women of virtue. While many of the values promulgated by these stories, such as bravery and honesty, are timeless, others can seem dated or run counter to modern mores. Since the mid 20th century, the genre of Fractured Fairy Tales has emerged that retells or rewrites fairy tales, often with a feminist or comedic bent. Perhaps the most famous attempt to rewrite the classic fairy tale is George Lucas’s Star Wars, which maintains classical models of heroes and villains but sets it against an intergalactic background, offering a princess who is both a cunning warrior and an independent-minded politician. Following this modern approach, the Akiva Grade 2 Readers Theater also included our students retelling classical fairy tales after presenting the original version. In keeping with our educational philosophy, Akiva always strives to give our students the best traditional learning in a modern and progressive mode. I am sure that Mother Goose would have approved.