Rabbi Grossman, Head of School

Chidushim B’Chinuch—Insights into Education

Fifth of an Ongoing Series

The great mysteries of the human condition are the topics of the first eleven chapters of the Torah. In Genesis 1-6, which we read in last week’s Torah portion, Scripture addresses the origins of marriage, clothing, work, and worship – all conventions that are unique to our species. Parashat Noach continues to expound on these etiologies, the last of which is the story of The Tower of Babel, found in Genesis 11. The final enigma the Torah addresses is, then, the origin of language. Are we to infer from this chronology that, of all riddles of existence, language is the greatest?

Perhaps. While matrimony, clothing, labour, and religion are distinct features of homo sapiens among God’s creatures, there are aspects of language that make it a particularly puzzling phenomenon. These elements are addressed in the Babel story. The narrative itself is brief:

Now the whole world had one language and a common speech.

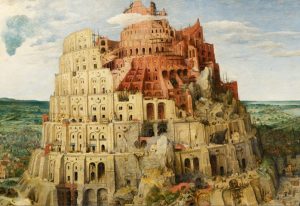

The Tower of Babel, painting by Pieter Bruegel (c. 1563)

Then they said, “Come, let us build ourselves a city, with a tower that reaches to the heavens…otherwise we will be scattered over the face of the whole earth.”

But the Lord said, “If as one people speaking the same language they have begun to do this, then nothing they plan to do will be impossible for them. Come, let us go down and confuse their language so they will not understand each other.”

So the Lord scattered them from there over all the earth, and they stopped building the city. That is why it was called Babel—because there the Lord confused the language of the whole world. From there the Lord scattered them over the face of the whole earth.

The tale begins with a pre-historic state during which all of humanity spoke one language, and ends with the present polyglot reality of multitudinous languages spoken throughout the world. The issue that the story seeks to address is, therefore, not so much why language exists, but why there are so many languages. Furthermore, buried in the pericope is the answer to a question that we ask as educators and parents—especially in Quebec: Why is it so difficult to learn a second language?

As with language, so too marriage, clothing, work, and worship present with great variation among different nations and populations. Yet with minimal effort we can easily understand other forms of wedlock and fashion, pick up new trades, and even convert to different faiths. But becoming fluent in a foreign language is famously difficult, involving hundreds, if not thousands of hours of learning, and extreme effort and dedication. This is all the more mystifying when we consider the ease with which we learn our first language: consider that even the most primitive and uneducated people can speak their mother tongue perfectly.

Our parasha addresses this quandary by explaining that the barrier to multilingualism was manufactured by God in order to accomplish a greater goal—the creation of diversity. By creating multiple languages and making it so difficult for people to understand each other’s speech, humanity was forced to form different and distinct nationalities, creating a pluralistic world.

In the thousands of years after The Tower of Babel, the Divine goal has been achieved. We live in a diverse world with over 200 countries and territories in every corner of the globe, speaking upwards of 6,500 languages. The objective now met, the difficulty of learning new languages remains.

Akiva Language Lab

At Akiva, we are doing our part to address this issue with our new Language Lab, which was officially launched this past Monday evening. The Language Lab is designed around a principle found in The Tower of Babel story, namely, that first languages are easy to acquire. The Language Lab uses modern technology to imitate the way that we learned our first language, making bilingualism as natural and enjoyable as acquiring our mother tongues. We are thrilled that our students will be the first in Quebec—and in North America—to experience this approach to language learning on the elementary school level. In doing so, we bring the lessons of our ancient Torah to the world of modern education.