Rabbi Grossman, Head of School

Chidushim B’Chinuch—Insights into Education

Sixth of an Ongoing Series

My decision to pursue a career in education was solidified in 1989 when I saw Peter Weir’s Oscar-winning film, Dead Poets Society. As far as I can remember, I wanted to become a teacher from the moment I first sat in a classroom. But Robin William’s performance convinced me of the power of literature to elevate life, and the role a teacher can play in unlocking the greatness of the written word. The important place the movie played in my teenage life (I somehow obtained a theatrical poster that hung in my bedroom throughout my high school years) is all the more significant in that, previous to viewing the film, I had no interest in poetry.

The theatrical poster that hung in my room during high school

Poetry is an elusive form of writing. On the one hand, it is most unnatural. A line from Molière’s play Le Bourgeois gentilhomme that I quoted in this blog last year sums it up nicely:

« Par ma foi ! il y a plus de quarante ans que je dis de la prose sans que j’en susse rien !»

“My faith! For more than forty years I have been speaking prose while knowing nothing of it!”

That is to say, prose is the natural form of language, so much so that we are completely unaware that we use it (almost) exclusively when we communicate. Poetry, on the other hand, presents itself as a foreign style of expressing our thoughts. When reading or listening to poetry we are justified in feeling (per Molière), that no one talks that way.

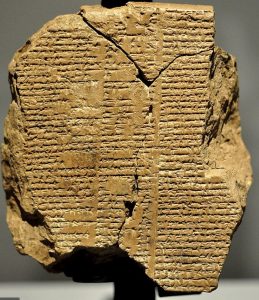

It is a great paradox, then, that poetry is believed to be the oldest form of literature, perhaps pre-dating writing itself. We have examples of poetry from over twenty-five centuries ago, and some of the greatest surviving forms of Western literature are the epic poems of Homer and the four-thousand-year-old Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh. How are we to reconcile the oversized role of poetry in the history of literature with its foreignness in everyday life? I would like to offer one theory which is significant to the history of education and the practice of teaching and learning.

Tablet containing the poem Epic of Gilgamesh, believed to be the oldest surviving piece of Western literature.

Unlike other ancient epics such as The Iliad and The Odyssey, the Bible is mostly written in prose. However, whenever emotions or ideas become heightened and exalted, Scripture lapses into poetry. For example, when Jacob is told that his beloved son, Joseph, has been killed, Jacob suddenly begins to speak in poetry, spontaneously uttering a two-line couplet of grief. As well, when the Israelites miraculously cross the Sea of Reeds, they break out in unison with the poem known as the Song of the Sea. So too, the books of Psalms, Lamentations, and Song of Songs, collections of prayers, eulogies, and love poems respectively, are all written in verse. When people are moved by passion—for God, for sorrow, or for ardor—their writing rises from prose to poetry. Poetry, is, therefore, writing at its highest level of passion.

The style of poetry mimics its substance: As poetry expresses a higher emotional register, it becomes more syntactically complex as well. This is among the reasons why poetry is more difficult and inaccessible than prose. Poetry therefore offers us access to the loftiest form of human expression, but at the cost of having to decode its complicated form and structure.

There has been a movement in progressive education for at least 50 years to stop teaching difficult literature in schools (such as classics and poetry) and instead expose students to more accessible and modern works. The argument is that students will read more if what they read is easier to understand. While getting students to read more is certainly a laudable goal, I am not convinced by this strategy. Outside of school students should certainly be directed to read books that they find enjoyable, understandable, and entertaining. School, however, is a place where children can be given the skills to appreciate the best and highest level of literature. This is why, in revising our English curriculum at Akiva, we are introducing more poetry and traditional literature. This year we began teaching Shakespeare as part of our 6th grade English course, and dedicated this year’s Common Read to poetry. Poetry and all sophisticated literature can be brought to life with the right teacher, and we are blessed at Akiva to have such inspirational teachers. It is not just in the movies.