Rabbi Grossman, Head of School

Chidushim B’Chinuch—Insights into Education

Seventh in an Ongoing Series

As a child, neither my friends nor I were afraid of monsters or vampires, and I know whom to thank. When children of a previous generation imagined monsters or Gothic villains they would think of Frankenstein’s monster or the sinister Count Dracula; my contemporaries and I envisioned furry felt puppets with googly eyes. The monsters and vampires of my youth were not scary beings, but lovable Grover, Cookie Monster, and (my favorite), Count von Count. For sparing me this juvenile trauma, I can thank Sesame Street.

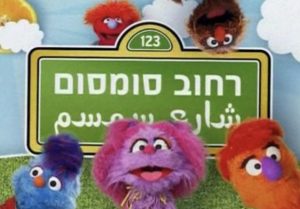

Israel had its own version of Sesame Street: Rechov Sumsum

Sesame Street turned 50 this past weekend. Finding a fun way to free children of their fears was just one of the many educational innovations of the Children’s Television Workshop when it launched its flagship show on November 10, 1969. Sesame Street was not the first educational television show but rather the first children’s show to use educational theory and data-driven research to deliver educational content. On Sesame Street’s 25th anniversary, Professor Kay Hymowitz described the rigorous intellectual discipline that went into making the program both instructive and entertaining:

During the show’s development, a group of eminent child experts formulated a curriculum according to the latest academic theories about children’s cognition. They came up with a list of skills collected under categories like “symbolic representation” (letters, numbers, geometric shapes), “relational concepts” (up and down, near and far), and “perceptual discriminations” (identifying body parts). At the same time, another group of experts was at work figuring out how to keep kids’ eyes on the screen. By using a “distracter” test—a slide show placed next to the television to determine at what moments fidgety viewers turned away from the TV screen—they discovered the power of visual pyrotechnics like fast-paced action and frequent cuts…

Sesame Street added Canadian content when it aired on CBC: Here a moose explains the Canadian Quarter

When Sesame Street premiered, society was facing many of the same challenges we confront in the 21st century, such as how to cope with seductive technologies that enticed young and old alike. Our children today spend, on average, upwards of 35 hours each week on screens; in 1969 the norm was not significantly lower (30 hours per week) though of course it was exclusively in front of the television tube and not divided among devices. Like many contemporary educators, the creators of Sesame Street decided not to engage in the almost-certainly futile luddite rejection of this new electronic medium, but rather to see how its power could be harnessed to enhance student learning.

The diverse stars of Sesame Street

At Akiva, we often follow this approach: in our Innovation Lab, Language Lab, and with our classroom Smart Boards, we use screens and other technologies to improve how our students learn. At the same time, we are skeptical of the over-use of screens and limit our students’ exposure to devices during school hours. Indeed, there has been much criticism of Sesame Street over the years for its embrace of TV and pop culture at the expense of in-depth learning. Sesame Street has been attacked for shortening children’s attention spans with its format of brief segments, and for making book-learning feel dull compared to its entertainment-based instruction.

And yet, Sesame Street must be commended for advancing so many of the goals and values we hold dear at Akiva. Sesame Street was ground-breaking in promoting and foregrounding diversity: both its human characters and Muppets were from every race and religion; they were blind and deaf, disabled and autistic. Big Bird represented an awkward child who was the wrong size for his age, and Ernie and Bert were designed to show how people of different colours could be best friends. Sesame Street was set in a poor neighbourhood; Mr. Hooper was Jewish.

Sesame Street also used experts in child psychology to guide them in creating content that would help children face difficult situations that other kids shows would not confront: When actor Will Lee died in 1982, Sesame Street did not recast the role of Mr Hooper but created a first-of-its-kind episode explaining death to children.

At Akiva, we share Sesame Street’s spirit of innovation, its embrace of diversity and its passion for educational research. In the words of its theme song, we also love learning and living in a place with “happy people like you.”