Rabbi Grossman, Head of School

Any child who has been called a troublemaker can take comfort in being the victim of the same accusation that was hurled against Elijah the Prophet (Eliyahu HaNavi). Ahab, the wicked King of Israel, dubbed Elijah the “Troubler of Israel” for opposing his policies of polytheism and idolatry. For his part, Elijah told Ahab that it was he, the king, who was causing trouble for Israel by leading them astray after false gods.

Elijah’s willingness to stand up for God even at great personal risk made him a great hero of the Jewish people. The ancient sages hypothesized that Elijah was a reincarnation of the priest Phineas, who, like, Elijah, was also a zealot and an intrepid defender of our faith.

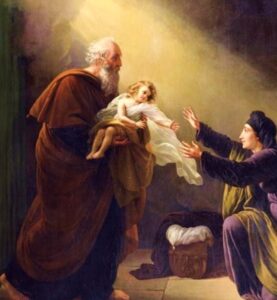

When we first meet Elijah, he is an itinerant miracle worker. He magically provides food for a poor widow during a drought by multiplying flour and oil in jars and jugs so that their supply never diminishes. He splits the waters of the Jordan river in half so that he can cross dry-shod; he brings a young boy back to life, being the first person in the Bible to revive the dead.

This past Shabbat (as every year on the Shabbat before Passover), the Scriptural reading concluded with the prophetic promise that Elijah would herald the coming of the Messiah:

הִנֵּ֤ה אָנֹכִי֙ שֹׁלֵ֣חַ לָכֶ֔ם אֵ֖ת אֵלִיָּ֣ה הַנָּבִ֑יא לִפְנֵ֗י בּ֚וֹא י֣וֹם יְהֹוָ֔ה הַגָּד֖וֹל וְהַנּוֹרָֽא׃

“Behold! I will send the prophet Elijah to you before the coming of the great and awesome day of the LORD.” (Malachi 3:23)

Elijah Restores a Young Boy to Life (painting by Louis Hersent)

Considering his biography, it is fitting that Elijah makes an appearance at the Seder. Elijah’s confrontation with Ahab echoes Moses’ audience with Pharaoh, with both encounters in defense of the God of Israel. Elijah’s preternatural provision of food recalls the manna that miraculously fed the Israelites in the desert and his splitting of the Jordan river recalls Moses’ splitting of the Sea of Reeds. Additionally, as I have written previously, the Hebrew month of Nissan in general, and the holiday of Pesach in particular, is an auspicious time for the coming of the Messiah and techiyat hameitim, the revival of the dead, both of which are connected to Elijah. As the Talmud relates, “In Nissan we were redeemed, in Nissan we will be redeemed again.” (Talmud Rosh Hashanah 11a)

I believe there is another reason why Elijah appears at the Seder. The Seder is a night of children and a night of questions: It begins with the youngest child asking The Four Questions, and continues with the four children, three of whom ask questions (one being too young to know how to ask!). There is a mitzvah, a commandment to encourage children to ask questions throughout the Seder, and the rituals of the night (such as serving unusual foods and removing objects from the table) are designed to provoke questioning in children.

By the end of the evening, many of these questions will be left unanswered. In Judaism we believe and accept that we do not have answers to some of the most fundamental questions of life and faith. A friend of mine approached me this year in anticipation of Passover and asked: how can we know that the story of the Exodus happened like the Torah describes it? When I shared the story of Elijah and his miracles with our students a few weeks ago, one young man shot his hand up in the air and asked, “Did that really happen?” Many of us have other fundamental questions about God, reward and punishment, the persistence of evil, and the human condition.

The past few years have intensified our questions. We ask ourselves what the next days or weeks will bring, what the world will look like in a month, in a year. We ask what lasting effect these past years will have on our children—will they be more challenged, or more resilient? We ask what normalcy is, and when it will return to our lives. We ask when God, who has rescued us in the past, will again rescue us, and when God will save a world in need of redemption.

While we have learned to live in a world without answers, Elijah provides an antidote. There is an ancient tradition (Mishnah Eiduyot 8:7) that Elijah holds the answers to all unanswered questions, and that, at the end of time, Elijah will come and settle all unresolved matters.

The Fifth Cup: To Drink or Not to Drink?

This is related to the Cup of Elijah that is poured after the meal. There was a debate among the rabbis whether four or five cups of wine should be drunk at the Seder. In the end, we drink four cups and pour a fifth. Since we are unsure whether this cup should be drunk, we call it the “Cup of Elijah” since he will be the one to resolve the dispute and tell us whether or not to drink the fifth cup.

As we get older, we learn to live with unanswered questions; but children seek answers. As adults, we are often bothered by these questions, frustrated with our inability to provide answers for our children. It is for them that Eliyahu appears. Maybe not this year, but we can assure our inquisitive sons and daughters that, one day, he will arrive and answer all of their questions. As the Troubler of Israel himself, he has a profound empathy for the troublesome questions that children often ask.

For Elijah, who will lead our children to the Final Redemption, they and their questions are no trouble at all.