“Do you have a 14”x14” box?” I ask the lady at U-Haul. She shows me her three different sizes, but the closest is 16”x12”. I think about it for a few minutes, looking around the store, trying to ascertain whether the box will meet my needs. “Ok,” I decide, “I’ll take the 16×12.” “How many would you like?” she asks. “Oh, just one” I answer. I suppose it’s rare to come to a moving supplies outlet and buy one single box of a specific size, but I pay her $1.50, and leave the store, pleased with myself for accomplishing the task my youngest daughter had assigned me.

“Do you have a 14”x14” box?” I ask the lady at U-Haul. She shows me her three different sizes, but the closest is 16”x12”. I think about it for a few minutes, looking around the store, trying to ascertain whether the box will meet my needs. “Ok,” I decide, “I’ll take the 16×12.” “How many would you like?” she asks. “Oh, just one” I answer. I suppose it’s rare to come to a moving supplies outlet and buy one single box of a specific size, but I pay her $1.50, and leave the store, pleased with myself for accomplishing the task my youngest daughter had assigned me.

After seeing a video online, we had decided together to make a café for her Barbies. We had already made a list of supplies we needed, and we had shopped at Michael’s for scrapbook paper for the floor and counter, but we were missing the box – the fundamental component to form the café structure.

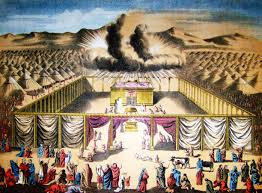

In this week’s parashah, Terumah, God tells Moses to ask the Children of Israel to voluntarily donate for God a portion of various materials – gold, silver, copper, turquoise, purple and scarlet wool, linen, goats’ hair, ram skins, wood, oil and spices. God explains:

“They shall make me a Sanctuary – so that I may dwell among them – in conformance with all that I show you, the form of the Tabernacle and the form of all its vessels; and so you shall do.”

The remainder of the parashah provides tremendous details as to how the various components of the Mishkan (literally, “the dwelling,”) – the ark, table and menorah – are to be constructed, specifying materials and dimensions. (But without the YouTube video).

Why did God want the Israelites to build a physical structure to house or represent His divinity. Should not the people have understood that God is always among us? Can we not find God wherever, whenever we seek Him out? What are we meant to learn from this elaborate construction of – essentially – a (very fancy) portable, temporary empty box?

Over the centuries, most commentators grappled with these very questions. Many looked ahead in the narrative to the story of the golden calf, when Moses – their leader and the personification of the nation’s relationship with God – has been gone on Mount Sinai for a long time and the people convince Aaron to cast a golden calf for them to worship, directly transgressing one of the Ten Commandments.

By commanding the creation of the Mishkan, God is providing a solution before the problem or sin has yet to occur. He anticipates that the people need a concrete representation of God’s presence in their lives.

All the instructions for construction suggest that the project encouraged a sense of community and “working together for a common goal.” After so many complaints to Moses about their food and water and safety in the desert, the Israelites seem to have surrendered their narcissism with focused physical labour. Perhaps God’s intention was to further the transformation of this group of runaway slaves into a nation through a purposeful collaborative effort.

So while there are various ways of understanding why God tasked the Israelites with this special (crafty) building project, God’s editorial remark – so that I may dwell among them – begs further thought. How do we find God in an empty space we’ve created ourselves?

A newly-laid wood floor is going to have its first scratch, a freshly painted wall, its first mark or dent. These are the physical details we may choose and pay for and perhaps even labour over ourselves, but they are a concrete physical exterior subject to the elements of nature and human error of which we have no control. Similarly, the Israelites made no contribution to the design of the Mishkan. They had no control over how to build it. They were only following instructions.

Three weeks into my eldest daughter’s NICU stay, the IV in her foot infiltrated and the subsequent wound needed to be treated by a special dermatological team. They came each day to change the dressing and apply special creams, but nonetheless, she was left with a permanent scar that grew proportionally with her foot.

I remember how devastated I felt at the time that this perfect baby was now blemished. I had been the last one holding her prior to noticing the funny angle of the IV when she was back in the incubator – how could I not blame myself for “damaging” her?

A child is a miracle of God’s creation, the product of many myriads of details – cells and genes and organs – to which we contribute but over which we have no control. What we learn from “so that I may dwell among them” is the potential for how we choose to fill the space we’ve been given. Whether it be a child, or a house, or simply an empty box – the outside is irrelevant. But when we fill this entity with love, with experiences, with values, with imagination, with celebrations and compliments and encouragements, then we find God among us. Then we have infused meaning and sanctity into our lives.

My daughter and I worked together to create our Barbie Starbucks. The empty box is completely transformed from the instructions we followed on YouTube. And while the Barbies drink their lattes, we’re planning our next project. Because we, too, are transformed from seeing the possibilities in empty boxes.

Shabbat Shalom.