Deborah Abecassis Warshawsky.

Carb-free, fat-free, gluten-free, sugar-free, dairy-free, meat-free. Many of us, at some point, have resolved to drastically change the way we eat from one day to the next.

Each Monday morning, people everywhere are cutting out everything they are used to eating in hopes of getting healthier, thinner, fitter… happier?

Eliminating birthday cake seems simple until you’ve hosted a room full of 5-year-olds and the frosting is just the “pick-me-up” you need. Giving up challah at the beginning of the week feels like – well – a piece of cake, until Friday rolls around and it’s freshly baked and smells amazing and you deserve a reward for making it to the finish line.

Many manage to stick to their new plan for a little while – until life throws a curve-ball, until we get too busy and miss a meal, until snacks appear at work, until a meltdown over homework, until 3:00 PM.

Change takes practice and most people revert to what is known and comfortable when routine and the expected dissolve into the extraordinary and chaotic. And for many, that happens at some point every single day.

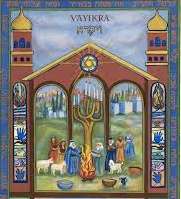

This week’s parashah is the start of the book of Vayikra, and we are introduced to the different sacrifices the Israelites can offer before God in their new Mishkan. Briefly and simply, the burnt offering was the standard sacrifice in which an animal was completely burnt on the altar, and neither the priest nor the one offering the sacrifice could partake of it. The idea that the animal is completely consumed by fire can suggest that the offerer is devoting himself wholly and completely to God.

The meal offering consisted of flour, oil and incense. Half of this offering was put on the altar and the rest was reserved for the priests. A meal offering was required with every animal sacrifice.

The peace offering was often brought with joy to fulfill a vow. Portions of the animal were burned on the altar and shared with the priests, and the remainder was eaten by the one who brought the offering and his family.

The sin offering was brought to absolve an unintentional sin, and the procedure for making the animal sacrifice differed depending on the status of the perpetrator within the community.

Finally, the guilt offering was brought to absolve one of a sin involving the misappropriation of property. The sacrifice required a ram to be offered on the altar, but only after the perpetrator repaid what was taken, along with an additional fine.

Sacrifices ceased to form part of our ritual when the Temple was destroyed, and 2000 years later, in our animal-rights conscious world, it is challenging for us to truly grasp the role they played in the lives of the Israelites and the appeal they held for seeking connection to and absolution from God.

Maimonides, in his Guide for the Perplexed, offers a very practical, historical and psychological explanation for the purpose of the sacrifices in Israelite worship:

“It is impossible to go suddenly from one extreme to the other; the nature of man will not allow him suddenly to discontinue everything to which he has been accustomed” (Isadore Twersky, A Maimonides Reader, p. 328).

The Israelites in Egypt were accustomed to worship that involved animal sacrifices and burning incense before concrete images of deities. This is what they knew and this is the form of service and ceremony with which they were comfortable.

“It was in accordance with the wisdom and plan of God … that He did not command us to give up and discontinue all these modes of worship, for to obey such a commandment would have been contrary to the nature of man, who generally clings to that to which he is used…” (Isadore Twersky, A Maimonides Reader, p. 329).

So rather than take the Israelites out of Egypt and toss out everything they knew and which gave them comfort and connection, God, in His wisdom and understanding of human nature, incorporated the ritual with which they were familiar into their practice, but tweaked it. The Israelites were still to make offerings, but according to specific rules and within set guidelines, and obviously, only to God Himself.

Without this familiar outlet, this new form of monotheistic worship for the Israelites would have been at risk of failing, as they would have likely turned to sacrifices each time they encountered hardships in their desert trek.

Successful change happens slowly, with small steps, holding close the elements we treasure and even need. Not everyone agreed with Maimonides’ conception of the place of sacrifice in Israelite worship, but his reflections on human nature and its resistance to relinquishing that which we know are undeniable.

Ironically, we must be open to making “sacrifices” (not the animal kind) in order to bring about change. But we must be cognizant as well of our own realistic limitations. We must build from the good and gently, but consistently, tweak the details we want to improve.

God demonstrated an extraordinary respect for the Israelites’ history and experience prior to the Exodus from Egypt. We learn from this that change for ourselves or for others requires that same respect for what exists now in the present, before we can expect progress in the future.

Challah – full of carbs and gluten and sugar – will always be on our Shabbat tables. Respect it. Include it. Enjoy it. It is nourishment for the spirit and perfect exactly as it is.

Shabbat Shalom.

An Akiva parent, Deborah has an MA and PhD in the history of Jewish Bible Interpretation from McGill University as well as a Masters in Library and Information Science (MLIS) also from McGill.