We have this new game we’ve been playing called Snake Oil. One person is the customer and chooses a card that provides this player with an identification or an occupation. For example, she might be a tourist or a rock climber, a nurse, a camp counsellor, or a Pharaoh (and there are endless more). The remaining players are merchants. They each take 5 word cards and must combine two cards to invent something they try and sell to the customer. Burp glasses, perhaps? A snore balloon? Maybe a ghost camera?

We have this new game we’ve been playing called Snake Oil. One person is the customer and chooses a card that provides this player with an identification or an occupation. For example, she might be a tourist or a rock climber, a nurse, a camp counsellor, or a Pharaoh (and there are endless more). The remaining players are merchants. They each take 5 word cards and must combine two cards to invent something they try and sell to the customer. Burp glasses, perhaps? A snore balloon? Maybe a ghost camera?

The fun and creative (and shhh, educational) part of the game is the thinking process required to pitch your invention successfully. The merchants must understand what the customer does, where the customer might encounter challenges in her occupation, what would make her day easier, safer, more successful, what would help her feel good, and what might capture her imagination.

The merchant also must figure out how to formulate and articulate her words carefully and convincingly, with a certain degree of humility and respect. The player of this game (unknowingly) learns to sharpen her skills in persuasive arguing, read her audience and gage what would be the most lucrative mix of audacity and indulgence.

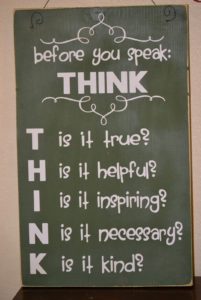

There is a delicacy and art as well as tremendous power in our use of words.

Parashat Metzora continues to relay the laws and rituals regarding the tzara’at. Last week, the Torah described the signs of one who is afflicted. This week we learn how the afflicted person is purified by the priest, and the process through which the priest decides whether an afflicted house can be purified or must be demolished.

The Lord spoke to Moses and Aaron saying: When you arrive in the land of Canaan that I give you as a possession and I will place a tzara’at affliction upon a house in the land of your possession, the one to whom the house belongs shall come and declare to the Kohen, saying: Something like an affliction has appeared to me in the house.

Rashi’s commentary addresses a single letter in the verse, translated as “something like,” and wonders why the Torah specifies the language with which a lay person is to alert the Kohen of a suspicious blemish.

Rashi explains that even if the homeowner is a learned scholar and knows without a doubt that what has appeared on his wall is tzara’at, he should not render judgment and say, definitively, “An affliction has appeared.” Rather he should say, “Something like an affliction…”

Many questioned Rashi’s commentary on this verse. Some felt Rashi’s clarification was redundant since the power to pronounce something ritually “pure” or “impure” lay only in the hands of the priest. Even if an educated, knowledgeable person pronounced with authority that there was an affliction on the wall, he would have no power to alter the spiritual state of the building. Only the priest has that authority.

Others wondered whether this was an issue of superstition, lest one invite misfortune or an “evil eye” by naming a situation before the priest has assessed the blemish with his expertise.

Certainly, one could appreciate that the Torah may be guiding us to show humility and modesty before one whose expertise is to evaluate each blemish and assess whether its bearer’s spiritual state is altered.

It speaks to how we address our doctors when what we found on Google contradicts the medical advice we asked of them.

It speaks to how we address our teachers who spend long hours with our children and may experience a side of them we do not see at home.

Language is very precise and the words we choose and the tone we use greatly alter the message we convey.

Rashi sees the qualification “something like” as reminding the general public that the tzara’at is not a physical disease that can be diagnosed by Israelites, learned or not. The affliction emanates from God and therefore, the diagnosis can be rendered only by His direct emissaries.

The Torah enjoins the Israelites to be precise in the language that they choose and to respect the sacredness of the process and the duty of the priests.

We can accomplish so much more – with goodwill and cooperation, for the benefit of all – when we use our words carefully.

When the words we choose honour the people to whom we are speaking, we also honour ourselves.

Language is a skill and an art. And very powerful.

How would you sell a tourist a snack compass?

Shabbat Shalom.