The last thing I feel like doing the day after Passover is think about food. Again. There are so many important and meaningful messages to the holiday – about freedom and family and community, about faith and courage, traditions, history and heritage.

The last thing I feel like doing the day after Passover is think about food. Again. There are so many important and meaningful messages to the holiday – about freedom and family and community, about faith and courage, traditions, history and heritage.

But let’s face it – we spend an inordinate amount of time thinking about food. Planning and shopping and cooking and eating unleavened food. In truth, there’s no real reason our eating habits should change so dramatically. Current eating trends encourage us to eat mostly protein and vegetables – both of which are perfectly fine for Passover.

And yet, Passover makes us anxious as we alternate between being overly stuffed from Yom Tov meals and wondering whether we’ll find enough to eat and satisfy us.

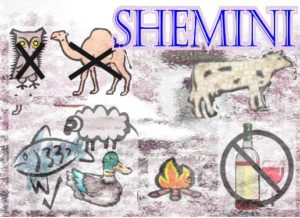

In parashat Shemini, following right after the holiday, God details for Moses all the animals that are and are not permitted for us to eat.

Speak to the Children of Israel, saying: These are the life forms that you may eat from among all the animals that are upon the earth.

Those that we are not permitted to eat are described either as “impure to you” or “an abomination to you” – neither of which translates accurately into the English. The sense of dirty that is conveyed in the nuance of impure, for example, does not reflect the ritual state of being intended in the Hebrew term “tameh.” Nonetheless, many commentators and scholars throughout the generations have tried to explain the reasons for which some animals were deemed “kosher” – a term that does not actually appear in the parashah at all – or not.

The rabbis of the Talmud classified this commandment as a “chok” – a law for which there is no reason given in the Torah or no obvious rationale. God said we had to eat this way and therefore, we should.

Others have suggested medical or spiritual benefits to the individual or a means for keeping the Jewish community separate and thereby sustaining our identity and strengthening our unity. Ultimately, though, these explanations are only speculation. At source, no reason is given.

And there will be those who choose to follow the commandments and those who choose not to.

But perhaps there is no explanation for a reason. Every individual must determine a personal meaning for incorporating this commandment into his or her life. And like many Jewish observances, we are left to decide how our personal choices will bring us closer to or further from community, family and other people in our lives.

We can step away from talking about food – finally – and think about the people around us: how to treat them as we wish to be treated, how to ensure we all feel included and respected.

How to savor the precious time we have with the people in our lives, rather than the food we can or cannot share.

Shabbat Shalom.