At about two or three-weeks-old, my daughter developed a hemangioma on her head. This benign swelling of blood vessels grew over the course of her first year into a significant and noticeable bump at the very top of her forehead. No matter how big and sparkling were her blue eyes, no matter how much personality radiated from her smile, this blemish was the first thing everyone noticed about her.

At about two or three-weeks-old, my daughter developed a hemangioma on her head. This benign swelling of blood vessels grew over the course of her first year into a significant and noticeable bump at the very top of her forehead. No matter how big and sparkling were her blue eyes, no matter how much personality radiated from her smile, this blemish was the first thing everyone noticed about her.

Of course the doctor told us it was nothing to worry about, that when she turned one-year-old, it would start to shrink, that hemangiomas are not uncommon, that some unfortunately grow them on the face, or in places that could interfere with breathing, and that it will be gone before she was ready to start school. All this information was good news, but it did not alleviate my anxiety or temper my discomfort.

And these feelings had only a very little to do with my baby and the bulge on her head.

I was distressed about the potential for a stigma. I did not want the responsibility of making everyone else around me feel better about the hemangioma. I didn’t want to have to worry about their worries, to defend the doctor’s prognosis, to help others feel less uncomfortable around this “deformity.” Do I pre-empt with an explanation, do I wait and see if they ask?

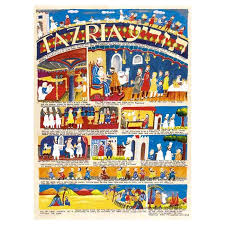

This week’s parashah, Tazria, is the first of two parshioth that address the role of the priest in identifying a skin disease referred to as tzara’at. Often translated as leprosy, the ailment manifest in many different forms and could also appear on one’s clothing, belongings or house. When an Israelite would discover a blemish that could be tzara’at, he would consult the Kohen – the priest. Not the doctor or the healer. The priest, as the keeper of the rituals and the means for attaining closeness with God was not offering a medical diagnosis but a religious or spiritual evaluation and reckoning.

Once the Kohen identified tzara’at on an individual, he would declare that person ta’me (often translated as impure or unclean):

And the person with tzara’at in whom there is the affliction – his garments shall be rent, the hair of his head shall be unshorn, he shall cover himself down to his mustache and call out, “ta’me! ta’me!” All the days that the affliction is upon him he shall remain impure; he is impure. He shall stay in isolation; his dwelling shall be outside the camp.

Although many commentators over the centuries have attempted to link tzara’at with a specific skin condition or disease, the Torah is not concerned here with issues of contagion and contamination. The book of Leviticus is also referred to in the Talmudic period as Torat Kohanim – or the Priestly manual – and thus was not intended as a medical handbook of ailments and cures. Rather it guides the priests in the specific rituals and procedures required to serve God.

According to the rabbis, tzara’at was the physical manifestation of God’s displeasure and evidence you had sinned. The role of the priests was to help the people regain favour and continue to serve God in a proper state of humility and devotion. The translations of ta’me and tahor as unclean or impure and clean or pure carry with them connotations and nuances and potential for stigma in English that I do not believe were intended in the Hebrew.

If the priest declared a person to be ta’me or tahor, this represented a spiritual state that dictated whether this person could participate in the rituals and ceremonies of religious practice. If they could not participate, they needed to be isolated so as not to diminish the sanctity of serving God.

When we remove the idea of cleanliness and purity as we understand these terms from the rules of tzara’at, I believe we have a clearer picture of the priestly responsibility and a less instinctual repugnance to the tzara’at. When we remember that the goal of the priesthood was how best to serve God, to uphold the rites and rituals and set a standard for devotion, the tzara’at is not a source of anxiety or embarrassment or disdain. It’s not a stigma.

I remember the exact moment I was able to reframe the hemangioma for myself. Describing it to a close friend, repeating the doctor’s diagnosis and expressing my dread of having to constantly address the reactions and concerns of friends and families, she said to me, “I know someone whose daughter had an enormous hemangioma when she was a baby, and I promise you she is now the most beautiful child I know.”

Because she is a friend who knows my heart, whose compassion responded to my anxieties on many different levels, I stopped seeing this birthmark as something I needed to handle, something to which I needed to react, but something that just was. Instead, I was able to refocus on the larger picture – my responsibility to nourish, protect and educate my baby (and not everyone else), and to have faith.

The birthmark began to diminish on her first birthday – almost to the day – just as the doctor predicted. And she continues to be (one of) the most beautiful child(ren) I know.

Shabbat Shalom.