There is a story told of Rabbi Akiva that the only time he ever said, “It is time to stop studying,” was on the eve of Passover and on the eve of Yom Kippur. He wanted to leave the house of study early on the eve of Passover “because of the children” – so they should not fall asleep before the seder. And on the eve of Yom Kippur, he wanted to leave early “because of the children” – in order that they may feed the children before the fast.

There is a story told of Rabbi Akiva that the only time he ever said, “It is time to stop studying,” was on the eve of Passover and on the eve of Yom Kippur. He wanted to leave the house of study early on the eve of Passover “because of the children” – so they should not fall asleep before the seder. And on the eve of Yom Kippur, he wanted to leave early “because of the children” – in order that they may feed the children before the fast.

The holiday of Passover and the seder are very much about the children and ensuring they learn the story of the exodus and embrace the responsibility of passing it on to the next generation. We read in the Haggadah:

In every generation, a person is obligated to regard himself as though he actually left Egypt. As it says: “You shall tell your son on that day, ‘It is because of this that God took me out of Egypt.'” (Exodus 13:8).

Without the children at the table, we’re not fulfilling our duty to tell them.

But Yom Kippur feels very different. For the most part, Yom Kippur is not about the children at all. It is the adults who fast and spend the day in prayer and self-reflection, and some would argue that caring for children on this day – feeding them, playing with them, supervising them – is only more difficult because of our weakened and distracted state. And yet, Rabbi Akiva suggests otherwise. His juxtaposition of Passover and Yom Kippur reminds us that our children should be at the forefront of one just as they are for the other.

Once there was a congregation assembled in the synagogue and ready for Kol Nidre as the sun set, but their beloved rabbi had not yet arrived. Concerned that something terrible must have happened to him, the congregants went to look for him. He was not in his home and he was not in the street or in the alleys. Just as they were about to give up, someone noticed a light in a window of a small shack. They looked inside and to their amazement, saw the rabbi seated by the side of a cradle and rocking it. “Rabbi,” they exclaimed, “we’ve been looking for you everywhere. It is past the time for Kol Nidre.” The rabbi, shushing his congregants, whispered: “On my way to synagogue, I heard a baby crying. When no one answered my knock, I entered and saw the baby alone. Since the child’s mother had evidently gone to the synagogue, I remained here to rock the baby to sleep and watch over him.”

Like Rabbi Akiva, this story reminds us that there is more to Yom Kippur than hearing Kol Nidre for yourself. While the connection of our children to Passover may be obvious, we must not neglect fostering their connection to Yom Kippur as well.

In my house, the discussion of the past few weeks was whether my youngest daughter would attempt to fast. Her sisters are both of Bat Mitzvah age and have fasted several times already, and as she has told me repeatedly, they started practicing when they were 9 years old like she is. She is not wrong. And she has a very reasonable plan. She’ll skip breakfast and then she’ll evaluate at lunch time how hungry she really is. “Obviously if I feel like I’m going to faint, I’m going to eat something,” she explains to me with a maturity far beyond her size.

In the Talmud, it states: “They do not cause children to fast on the Day of Atonement, but they should train them therein one year or two years before they are of age, that they may become versed in the commandment.” In another place, Rabbi Abaye reports that his nurse told him, “a child of six is ready to study Torah, a child of ten the Mishnah, a child of thirteen can fast for twenty-four hours and a girl can fast at twelve.”

She’s my baby without an ounce of fat on her and the thought of her not eating afflicts my Jewish mother kishkes. She also, however, has the logic of Maimonides on her side. The great Rambam explained:

At what age ought a child be trained to fast? A child who is fully ten years old and even one who is fully nine years old may be trained for a couple of hours. How? If he was used to eating at eight o’clock, he is fed at nine o’clock. If he was used to eating at nine o’clock, he is fed at ten o’clock. He ought to be made to fast according to his strength. The same is true of both boys and girls.

Ingraining in our children the sanctity and solemnity of Yom Kippur cannot begin only when they are old enough to fast. Like the Passover seder, they can and should experience and learn and understand a little more every year.

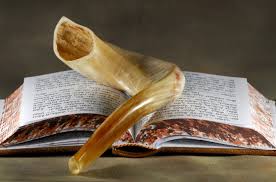

The shofar blowing at the end of Neilah is a powerful moment, and when I was younger and attended synagogue with my parents, my mother would hug me and wish me a Shana Tova. Now I too am compelled to hug my daughters. Relief that we have endured? Happiness at being together? Yes. The end of Yom Kippur is significant and emotional. And that too is something I wish to teach my daughters and which I’d like them to carry on.

There is a custom to bless our children on erev Yom Kippur before we leave for synagogue. In addition to the traditional blessing we recite on Shabbat, we say the following:

May it be the will of our Father in heaven, that He instill in your heart His love and reverence. May the fear of the Lord be upon your face all your days, in order that you not sin. May your craving be for the Torah and the commandments. May your eyes gaze toward truth; may your mouth speak wisdom; may your heart meditate with awe; may your hands engage in the commandments; may your feet run to do the will of your Father in heaven. May He grant you righteous sons and daughters who engage in the Torah and the commandments all their days. May the source of your posterity be blessed. May He arrange your livelihood for you in a permissible way, with contentment and with relief, from beneath His generous hand, and not through the gifts of flesh and blood; a livelihood that will free you to serve the Lord. And may you be inscribed and sealed for a good, long life, among all the righteous of Israel. Amen.

We wish for our children the continuity of all we hold dear, that they uphold the Torah and its teachings and our traditions. Even if they are still too young to participate in the positive and negative commandments of the day, we learn that we must care for them, teach them and involve them in the same way as we do for Passover.

And then when you hug them as the shofar blows and the fast ends, know that you have touched their heart and opened their soul to connect with the meaning and holiness of Yom Kippur.

Wishing you a Shabbat Shalom and a Gmar Chatimah Tovah.

May you and your families be sealed in the Book of Life.