Please enjoy this beautiful dvar Torah from Camp Ramah in New England!!

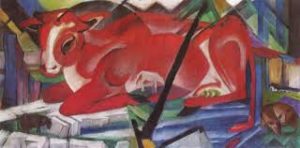

Parshat H ukkat begins with a profoundly strange ritual to moderns. We must sprinkle the ashes of a brown (“red”) cow on a person who has been contaminated by contact with a dead body. Of course without a Temple, we no longer perform this ritual, but how do we think about it today? The question of the origin of this ritual is interesting, but for contemporary Jews, it begs a more compelling question: How do we think about rituals for which we have no obvious rationale? What do we do with mitzvoth whose raison d’etre eludes our intellects? We can learn a lot about this question from the example of the parah adumah (the brown cow ritual), a topic that our scholars and have discussed since our first commentaries on the Torah were written.

ukkat begins with a profoundly strange ritual to moderns. We must sprinkle the ashes of a brown (“red”) cow on a person who has been contaminated by contact with a dead body. Of course without a Temple, we no longer perform this ritual, but how do we think about it today? The question of the origin of this ritual is interesting, but for contemporary Jews, it begs a more compelling question: How do we think about rituals for which we have no obvious rationale? What do we do with mitzvoth whose raison d’etre eludes our intellects? We can learn a lot about this question from the example of the parah adumah (the brown cow ritual), a topic that our scholars and have discussed since our first commentaries on the Torah were written.

One of the most fascinating answers to this question comes from Numbers Rabbah, a collection of midrashim that answers questions about the Torah and provides homiletic interpretations of the book of Numbers. The midrash relates a story in which an idolater approaches Rabbi Yochanan Ben Zakai and argues that the ritual of the parah adumah appears to be witchcraft, something that is absolutely forbidden by the Torah. Of course the larger implication of his assertion is that Judaism is just another form of idolatry, as it has the trappings of magic and strange manipulations of the natural world. Rabbi Yochanan Ben Zakai satisfies this idolater with a clever answer, and he subsequently leaves the rabbi’s presence. His students, however, remain in the beit midrash with their teacher. They say to their rabbi, “Master! You put him off with a reed, but what explanation will you give to us?” To wit, they have the same question as the outsider, but because they know so much, they know that his answer to the idolater is insufficient. The question remains on the table; his students can now express their surprise at the seemingly magical aspect of this ritual. His response is captivating: “By your life! The dead do not make one impure, and the water does not purify. Rather, the Holy One, blessed be He, merely says: ‘It is a ritual law that I have enacted; it is a decree that I have decreed.’ You may not transgress my decree, as it is written (in Numbers 19:2), ‘This is the ritual law that the Lord has commanded.’”

Essentially, Rabbi Yochanan Ben Zakai admits to his students that this is a ritual, not a magic spell. Impurity is a physical and /or emotional state that is identified by boundaries that we define, starting with the Torah. It is not a fact of the natural world. This ritual is important because we have a human need to move from the experience of impurity to purity, and without a ritual to usher us from one state to the other, we live in a constant experience of chaos, lacking clear boundaries that reflect our physical and psychological states. The ritual has meaning because we have understood it as a reflection of what we think God wants from us, not because the water or ashes in any physical way chase away our impurity! When we mark the moments of our lives in which we experience a return to our truer selves, a return to a state in which we feel that we can again connect to the world in an elevated way, we express our appreciation of and gratitude to God for allowing the boundaries to be fluid. Otherwise, we would live in elongated states of impurity, states in which we would feel disconnected from ourselves and the world in which we live.

Ritual is not magic, but rather an opportunity to bring myths and values into the world in real time. As professor Neil Gillman writes, “Myths function unconsciously. They are so ancient and authoritative that they become quasi-invisible. But those myths that shape human experience in a rich and distinctive way, that provide a living community with its raison d’etre and shape its sense of destiny cannot afford to remain invisible. They must be brought alive, into experience. To accomplish this, the community generates rituals. Rituals are public dramatizations that bring the myth into experience. They enable a community to bond together, live its myth in an overt way, and transmit it from generation to generation.”

The parah adumah reminds us of the importance of being conscious of the values and myths that our rituals are meant to bring into the world. It is this consciousness that is necessary for creating moments of sanctity and ultimately, bringing us closer to God. Religion is not scholarship. We are not interested in uncovering the original reason that spurred the ritual while we are in the middle of performing it. We are meant to recall the myth or value or narrative that gives the ritual meaning and sanctifies the moment, even if this myth is not the original catalyst for the ritual. So when we veil a bride at a wedding in the bedekken ritual, it matters not if the original ritual grew out of the story of Jacob accidentally marrying Leah instead of Rachel. What makes the ritual meaningful is that we recall this biblical story and take a moment before we stand under the chuppah to gaze into the eyes of our loved one with the intention of affirming that the love that we share is meant only for the person in whose eyes we gaze.

At Ramah New England, ritual has tremendous meaning, both traditional Jewish rituals and the rituals that we create each summer. Each night, every bunk stands together in a circle holding hands, and they sing a song to one another, thus ending the day, entering the night, and wishing one another a peaceful sleep. This ritual connects all of the campers to one another and reminds them that despite the quarrels and conflicts of the day, they share something special, something unique that they pray will not be lost as the sun sets. The parah adumah ritual ushered us into a state of purity when we experienced the harshness of the world. Human experience is made up of moments in which we feel pure, and moments in which we feel sullied by life. Marking the moments in which we move toward purity and holiness, both through Jewish rituals as well as the rituals we create in community, creates transformative life experiences. Such experiences bring us closer to our own humanity and G-d. Shabbat Shalom.